[ad_1] China has banned Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. It’s blocked Google and Bing. Zoom isn’t allowed. Even the ABC is deemed unsuitable for its c

[ad_1]

China has banned Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. It’s blocked Google and Bing. Zoom isn’t allowed. Even the ABC is deemed unsuitable for its citizens.

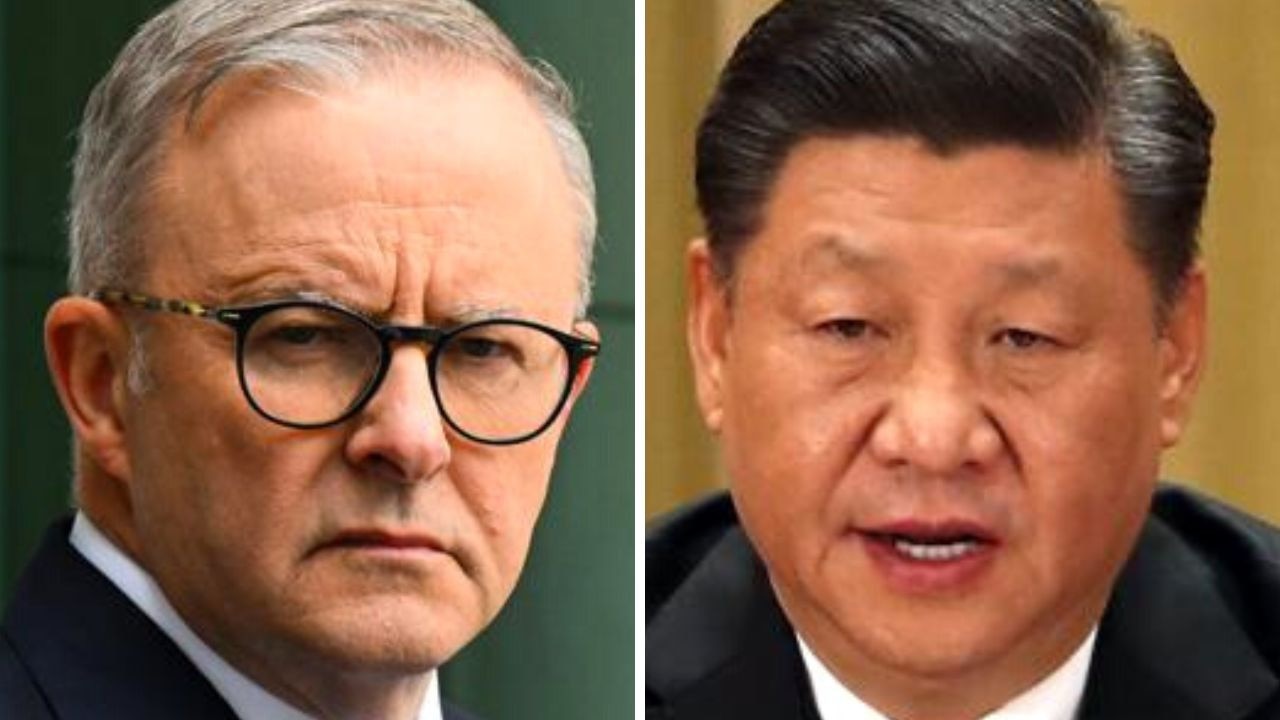

But Beijing’s quite comfortable threatening Australia not to “repeat its mistakes” and damage relations by sanctioning TikTok and WeChat.

This week, an inquiry into foreign interference with Australian politics and society concluded that Chinese-based social media apps like WeChat and TikTok could be compelled to “secretly co-operate with Chinese intelligence agencies”.

And this could be used to “corrupt our decision-making, political discourse and societal norms”.

As a result, Australia will consider extending its ban on TikTok from all government employee devices to contractors working on government projects.

And WeChat – which has similar access to user data as TikTok – faces the imposition of similar restrictions.

This has Beijing’s Communist Party-controlled media commentariat up in arms.

“At a time when China-Australia relations are at a critical juncture, Australia should not repeat the mistake it made in 2018 in banning Huawei from its 5G wireless network,” Hu Weijia warns in a Global Times editorial.

“Many see this decision as the spark that set off bilateral economic clashes.”

Hu did not mention the “Great Firewall” barring many Western businesses, services and social media apps from his own country.

But he was willing to use the threat of renewed sanctions to compel Australian compliance.

“If bilateral economic co-operation encounters challenges and difficulties again, Australian companies will become victims of setbacks in bilateral ties,” he wrote.

“The facts of the past few years have fully proven this point.”

Party games

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) insists all private Chinese companies include Party members on their boards. They must adhere to Party dogma. And that’s the law.

“China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law means the Chinese government can require these social media companies to secretly co-operate with Chinese intelligence agencies,” the report reads.

But the CCP’s corporate influence goes much further than that.

In 2020, Xi’s regime issued its Opinion on Strengthening the United Front Work of the Private Economy in the New Era. The Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) said this instructs the Party’s United Front Work Departments (UFWDs) to double-down on their ideological control of the private sector.

Commissars must “guide” businesses to “improve their corporate governance structure and explore the establishment of a modern enterprise system with Chinese characteristics”.

And that means “integrating the Party’s leadership into all aspects of corporate governance”.

The cost of any failure to comply was quickly demonstrated.

In December, Beijing launched an antitrust inquiry into tech giant Alibaba. Its high-profile CEO Jack Ma was “disappeared”. All because Ma dared to criticise the party-state’s manipulation of the banking sector.

The Senate Select Committee on Foreign Interference through Social Media report labels China-based messaging apps WeChat and Tiktok as “unique national security risks”.

Both social media platforms collect immense amounts of data on their users. Both use algorithms to influence what advertising and content a user sees.

And both have been accused of abusing the data they collected to suit their purposes – such as harassing journalists and critics.

TikTok tit-for-tat

The Senate report says countering foreign interference through social media is “one of Australia’s most pressing security challenges”. It makes 17 recommendations, including the threat of being banned in Australia if parent companies don’t establish a corporate presence here and conform to new operational transparency requirements.

TikTok said, “While we disagree with many of the characterisations and statements made regarding TikTok, on our initial reading, we welcome the fact that the committee has not recommended a ban. We are also encouraged that recommendations largely appear to apply equally to all platforms. TikTok remains committed to continuing an open and transparent dialogue with all levels of Australian government.”

WeChat has also issued a formal response.

“We are reviewing the committee’s report and recommendations in detail,” its statement reads. “As we communicated to the Senate committee, WeChat is committed to protecting user privacy and providing its users with a safe, secure and diverse platform for communicating with friends, family and businesses.”

WeChat told the Senate Committee that Beijing officials have never approached it to spy on its users.

But the inquiry was not convinced.

“WeChat showed its contempt for the parliament by failing to appear before the committee at all, and through its disingenuous answers to questions in writing,” its report reads.

And TikTok was so unwilling to talk that it even refused to admit its parent company, ByteDance, was based in China. But it did reveal its engineers can influence what users can see.

“In the case of TikTok, the committee heard that its China-based employees can and have accessed Australian user data, and can manipulate content algorithms — but TikTok cannot tell us how often this data is accessed despite initially suggesting that this information was logged,” the report reads.

Do as we say, not as we do

“(The report) tackles both the problems posed by authoritarian-headquartered social media platforms like TikTok and WeChat and Western-headquartered social media platforms being weaponised by the actions of authoritarian governments including Facebook, YouTube and Twitter,” Committee chair James Paterson said told reporters shortly after it was released.

Just hours later, Beijing issued its reply.

“If Australia allows itself to once again play a role as a vanguard to ban a well-known Chinese entity, it will send a wrong signal to the market, undermining market confidence in further improvement of bilateral economic and trade relations,” the Global Times editorial warned.

“Australia should avoid being kidnapped by US’ anti-China strategy. It is in line with the essential interests of businesses from both sides if the two countries continue to push economic and trade co-operation.”

But banning social media apps does come with a community cost.

WeChat is one of the few direct gateways through China’s Great Firewall. And that means expatriates, tourists and workers use it to stay in touch with friends and family.

“Many WeChat-using Chinese-Australians have not even heard about the proposal to ban it – but those of us who have are watching this space with mounting anxiety,” said University of Technology Sydney Professor Wanning Sun.

“WeChat is not merely an instant messaging tool, but a ‘super sticky’ app. It has been dubbed the ‘Swiss Army knife’ of social media.

“Facebook, WhatsApp and other Western social media are not allowed in China. This meant the uptake of WeChat soon reached near-saturation point.”

TikTok, meanwhile, is especially popular among young users.

“Despite what some may think, it’s not just a quirky app for dance videos,” said Swinburne University researcher Milovan Savic.

“TikTok has become a golden goose for millions of content creators who rely on the app as their stage to showcase their talents, build their brands and connect with fans and customers.”

But Paterson says there is clear evidence that social media can – and is – being used to manipulate political debate and social attitudes.

“These revelations do not bode well given that TikTok also admitted that its China-based employees cannot refuse to co-operate with China’s intelligence services under article seven of the 2017 National Intelligence Law,” he wrote.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel

[ad_2]

Source link

COMMENTS