[ad_1] In 2007, Premier Wen Jiabao cautioned that “the biggest problem with China’s economy is that the growth is unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinate

[ad_1]

In 2007, Premier Wen Jiabao cautioned that “the biggest problem with China’s economy is that the growth is unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable”.

He was referring to China’s penchant for over-investment, which was, in turn, driven by the unique Chinese urbanisation and its build-out of hundreds of millions of apartments.

This was the core of Australia’s iron ore boom as Chinese steel demand rose at astronomic rates.

Sadly for China, Wen’s warning went unheeded for another 15 years, in which time the construction rates of apartments tripled.

If 600 square meters of real estate was too much investment in 2007, then how would we describe 1750 square metres in 2021? As is often the case in Chinese statistics, words fail.

Making matters more bizarre, Chinese property statistics indicate that roughly 75 million apartments sold and started since 2007 were never completed.

This is enough to house 225 million people – at current rates, about ten years’ worth of urbanisation.

If that is anywhere near accurate, then Chinese property buyers have loaned developers about $16 trillion, for which they have not received anything.

It is a call on future property so large that, once again, there is no word for it.

Evergrande and friends

The developers have not built enough, but they have spent and borrowed plenty. Their business metrics make no sense to a Western analyst.

Average developer leverage in China is ten times their market capitalisation versus under one times in the US. For every $1 of sales, the median Chinese home builder owes $0.56 to suppliers and employees and $1.43 to people who have paid deposits.

These are insolvent firms running apartment Ponzi schemes of titanic proportions.

Beijing has been trying to reform this incredible mess for several years.

Its efforts have improved some developer metrics, but the market is far from what might be described as normal or sustainable.

Sales have fallen 40 per cent, but are still far too high. New construction starts by floor area have crashed 60 per cent. Yet the completion of apartments is relatively unchanged.

The mess is so toxic that consumers threatened a mortgage strike, and policymakers have resorted to funding the developers directly to finish swathes of pre-sold but unfinished stock.

No more growth for China

The data is sketchy to say the least, but we can draw some conclusions about what all of this means.

Property sales need to fall much further, and all of the public incentive is to avoid another round of stimulus buying.

The mess is far beyond too-big-to-fail. It is the linchpin of the entire Chinese economy, with the equivalent of 60 per cent of GDP tied up in unfinished buildings. So stimulus from here will focus heavily on completions.

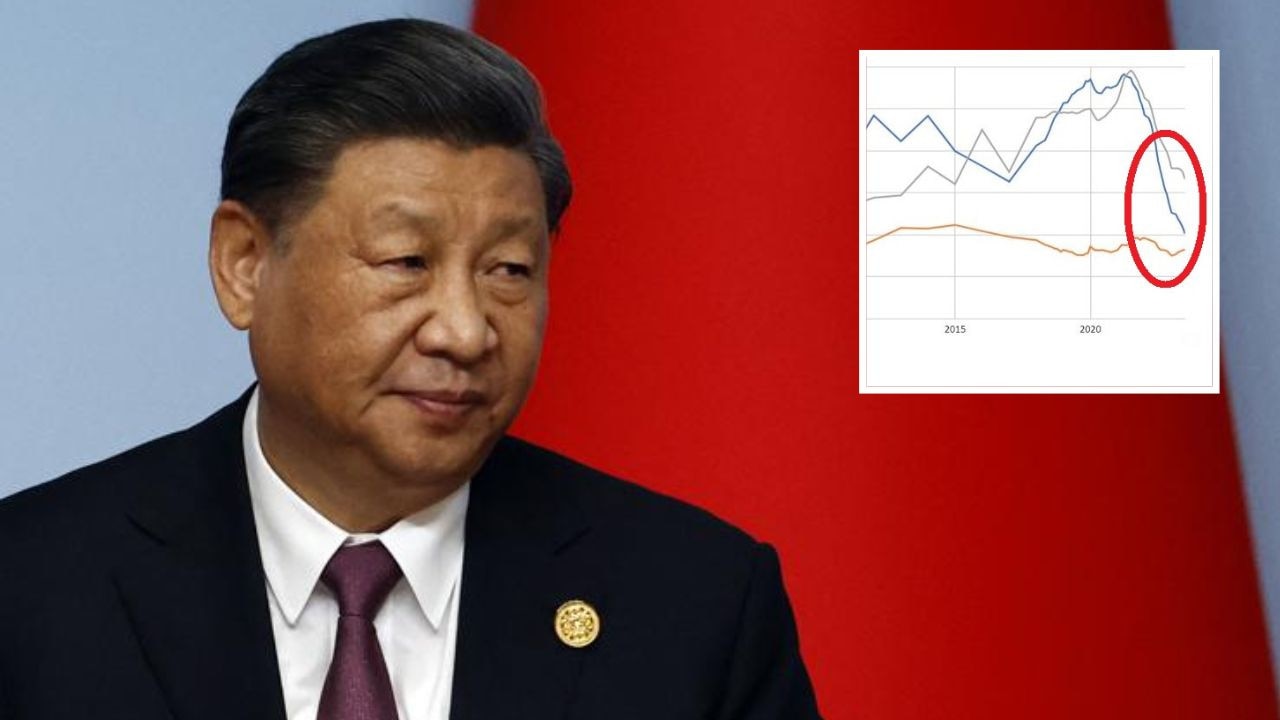

As such, the adjustment underway in real estate has ended the catch-up Chinese growth period. Ahead is ever-weakening growth as the 20-year construction binge winds down.

Chinese growth is already struggling to hit an imaginary 5 per cent target. If we calculate malinvestment properly, the reality is more like 3 per cent.

The last quarter was negative in nominal terms.

Steel yourself

This is the end of the iron ore and coking coal booms for Australia.

Chinese property consumed roughly 40 per cent of the nation’s steel output. When we combine infrastructure funded by land sales to the developers, it is more like 60 per cent.

Both will now be rationalised endlessly.

Thanks to the immense shadow inventory of sold but incomplete apartment stock, completions are more likely to fall steadily than to crash. Any estimate of how fast is a guess. Minus 5-10 per cent per annum seems reasonable.

This equates to 30-60 millions of tonnes less steel output yearly for as far as the eye can see, or 50-100 millions of tonnes of iron ore equivalent.

It may be hard to believe, but Australia has seen this before. A similar development trap closed around the Japanese economy in the late 80s as two decades of construction booms met declining demographics and a property bust.

Iron ore declined non-stop for a decade, reaching undreamed of lows before it was over.

History is repeating in China.

David Llewellyn-Smith is Chief Strategist at the MB Fund and MB Super. David is the founding publisher and editor of MacroBusiness and was the founding publisher and global economy editor of The Diplomat, the Asia Pacific’s leading geopolitics and economics portal. He is the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut and was the editor of the second Garnaut Climate Change Review.

[ad_2]

Source link

COMMENTS